How Misinformation Spread on Facebook During the 2020 Election: A Slow Burn Fueled by Peer-to-Peer Sharing

The 2020 U.S. election cycle was a tumultuous period marked by a global pandemic, political polarization, and a pervasive atmosphere of distrust in traditional media. The proliferation of "fake news" and misinformation became a central concern, raising questions about how false narratives spread and gained traction online. A new study from Northeastern University sheds light on the dynamics of misinformation dissemination on Facebook during this critical period, revealing key differences in its spread compared to other content.

Researchers analyzed Facebook posts shared between the summer of 2020 and February 1, 2021, including content flagged as false by third-party fact-checkers. Their findings, published in Sociological Science, reveal that misinformation spread distinctly differently from other types of content. While typical content often experienced a "big bang" distribution, rapidly disseminating through shares from large Pages and Groups, misinformation followed a "slow burn" pattern, gradually proliferating through peer-to-peer sharing among individual users.

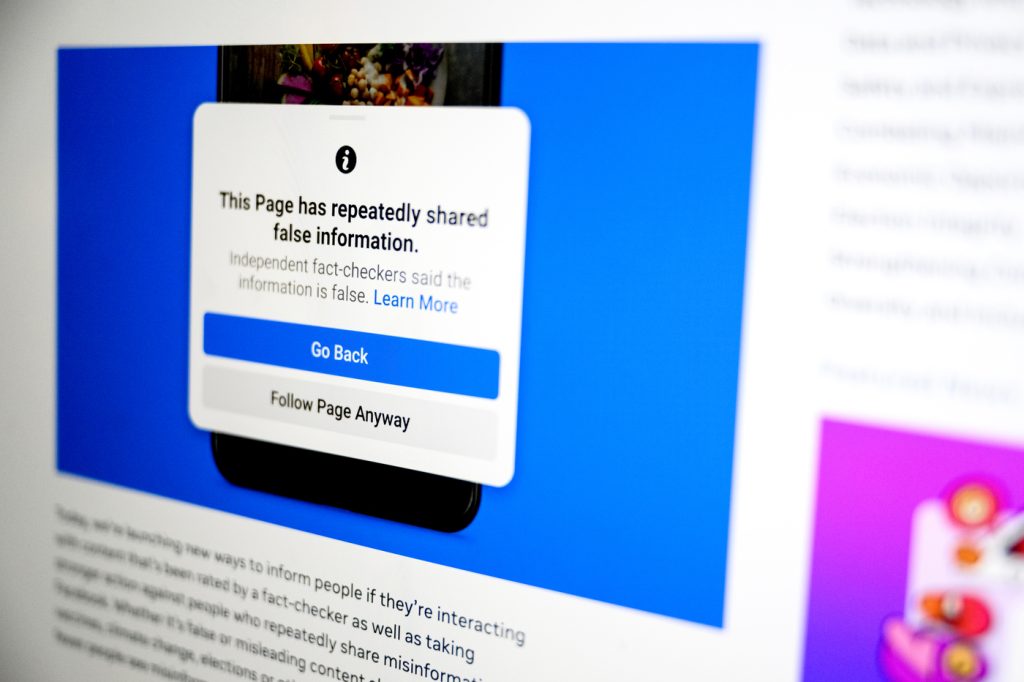

This difference in propagation patterns can be attributed to Facebook’s content moderation policies at the time. The platform focused its efforts on tackling misinformation originating from Pages and Groups, implementing penalties like reduced visibility for those spreading false information. Individual users, however, faced less scrutiny, creating a loophole for misinformation to spread through personal networks. This dynamic incentivized the shift from large-scale broadcasts of false narratives to a more distributed, person-to-person sharing model.

The study’s findings illustrate the effectiveness of Facebook’s targeted interventions. By cracking down on Pages and Groups, the platform successfully disrupted the traditional "big bang" distribution of misinformation. However, this also had the unintended consequence of driving the spread of false narratives underground, so to speak. Individual users, facing less stringent oversight, became the primary vectors of misinformation dissemination. This "whack-a-mole" effect highlights the challenges of effectively policing misinformation online, as platforms must constantly adapt to evolving tactics.

The research also identified a small but highly influential group of users – approximately 1% of the total user base – who played a disproportionate role in spreading misinformation. These "superspreaders" were responsible for the majority of reshares, demonstrating how a relatively small number of individuals can significantly amplify false narratives. This finding underscores the importance of understanding the motivations and behaviors of these key players in order to develop more effective countermeasures.

The study provides valuable insights into the evolving landscape of online misinformation. The shift towards peer-to-peer sharing necessitates new strategies for combating the spread of false narratives. While platform-level interventions targeting large sources of misinformation remain crucial, efforts must also address the decentralized and often more insidious spread of misinformation through individual networks. This may involve promoting media literacy, empowering users to critically evaluate information, and exploring ways to disrupt the influence of superspreaders.

The limitations of the study should also be acknowledged. The research focused specifically on Facebook and the 2020 election timeframe. Changes in platform policies, algorithms, and data access mean that a similar study cannot be conducted for more recent elections. Nonetheless, the findings offer important lessons for understanding the dynamics of misinformation and informing future efforts to combat its spread. The 2020 election serves as a case study in how misinformation can adapt and thrive even in the face of platform interventions, highlighting the continuing need for vigilance and innovative solutions.