Canadians Grapple with Distinguishing Truth from Falsehood in the Digital Age

The digital revolution has ushered in an era of unprecedented access to information, but it has also opened the floodgates to a torrent of misinformation. Canadians are increasingly relying on online platforms, including social media, for news and information, yet these sources are among the least trusted. A 2023 Statistics Canada survey revealed that over two-fifths of Canadians found it increasingly difficult to discern true news from false information, a concerning trend given that nearly three-quarters of Canadians reported encountering suspected false content online in the preceding year. This struggle to identify credible information underscores the urgent need to understand the factors that influence how individuals consume and share information online.

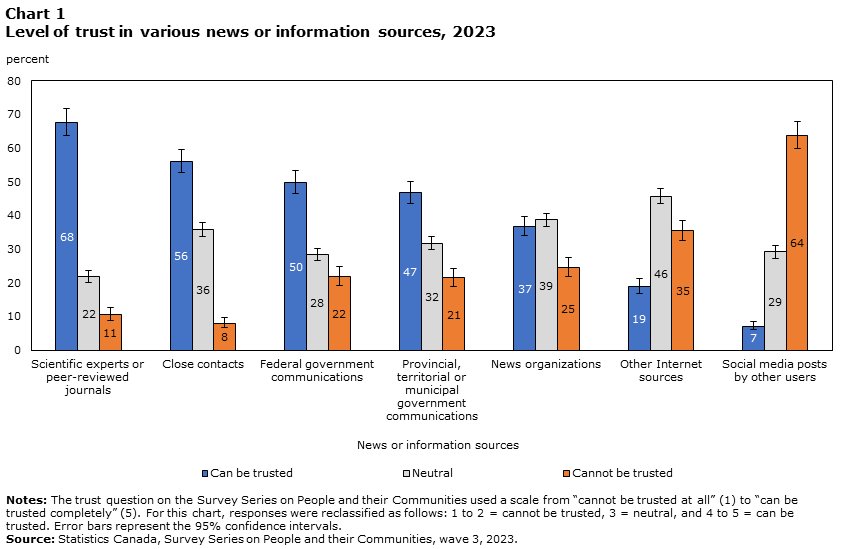

This article delves deeper into the dynamics of misinformation in Canada, drawing upon data from the Survey Series on People and their Communities (SSPC) and the Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS). The analysis explores the interplay between demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, and online behaviours related to fact-checking and sharing information. While Canadians generally place higher trust in sources like scientific experts and close contacts, social media platforms are viewed with significant skepticism. This distrust is not unfounded, as online platforms have become breeding grounds for misinformation, often propagated by malicious actors or through algorithmic amplification.

Fact-Checking Habits and Their Influencing Factors

The SSPC explored the prevalence of fact-checking habits among Canadians. Over half of respondents reported always or often verifying the accuracy of information, while a small minority admitted to never fact-checking. Among those who don’t consistently fact-check, a primary reason cited was a lack of interest or motivation. Further analysis revealed that age and education level were significantly associated with fact-checking behaviours. Older individuals were less likely to verify information, potentially reflecting a lower engagement with online platforms. Conversely, higher education levels correlated with a greater likelihood of fact-checking, possibly indicating a stronger awareness of information literacy principles.

Interestingly, mental health measures also played a role. Individuals expressing greater hopefulness were more inclined to fact-check, while higher life satisfaction was linked to a decreased likelihood of verification. This seemingly contradictory finding suggests that a sense of contentment might reduce the perceived need to scrutinize information, while a more forward-looking perspective encourages critical evaluation. Furthermore, individuals expressing concern about misinformation and those relying on expert sources or other internet resources were more likely to engage in fact-checking. This indicates that individuals actively seeking credible information are also more likely to verify its accuracy.

The Peril of Sharing Unverified Information

The CIUS examined the propensity of Canadians to share online information without verification. Approximately one in seven respondents admitted to sharing unverified content within the past year. Regression analysis again highlighted age and education as key factors. Older individuals were less likely to share unverified information, mirroring their lower fact-checking rates. Higher education was initially associated with a greater likelihood of sharing unverified information, potentially reflecting overconfidence in their ability to discern truth from falsehood. However, this correlation disappeared when controlling for prior exposure to misinformation, suggesting that education primarily influences the ability to identify false content, not the decision to share it.

Mental health, online habits, and prior exposure to misinformation also emerged as predictors of sharing unverified content. Individuals reporting better mental health were less likely to share unverified information, while increased time spent online and prior encounters with misinformation were associated with a greater likelihood of sharing without verification. This highlights the vulnerability of individuals immersed in online environments to misinformation exposure and subsequent propagation.

The Intertwined Impact of Age, Education, and Misinformation

Synthesizing the findings from both surveys, age and education emerge as critical factors in navigating the misinformation landscape. Older Canadians, often less engaged with online platforms, exhibit lower rates of both fact-checking and sharing unverified information. Higher education, while encouraging fact-checking, can also foster overconfidence in one’s ability to identify misinformation, leading to the unintended consequence of sharing unverified content. This underscores the importance of promoting critical thinking skills and information literacy education across all demographics.

The influence of mental health is complex and warrants further investigation. While hopefulness seems to encourage fact-checking, higher life satisfaction might paradoxically reduce the perceived need for verification. The emotional response to misinformation likely plays a significant role in both fact-checking and sharing behaviours, suggesting that emotional regulation and media literacy training could be crucial in mitigating the spread of false information.

Ethnic Variations and the Role of Social Media Platforms

The analyses also hinted at variations in online behaviours among different ethnic groups. The Chinese group showed a lower likelihood of fact-checking and a higher likelihood of sharing unverified information. This could be attributed to cultural factors, language barriers, or the use of distinct social media platforms with different information ecosystems. Further research is needed to explore the specific drivers of these observed differences and tailor interventions accordingly.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Both surveys relied on self-reported data, which is susceptible to biases. Respondents might overreport desirable behaviours like fact-checking, while underreporting less desirable ones like sharing unverified information. Furthermore, the surveys did not directly assess the ability to identify misinformation, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about the effectiveness of fact-checking efforts. Future studies should incorporate objective measures of misinformation detection and explore the sources used for fact-checking to understand how confirmation bias influences information validation.

Another avenue for future research is to examine how fact-checking strategies are employed and their impact on misinformation resilience. The Canadian Association of Science Centres’ Information Overload report highlighted the complex and iterative nature of truth-seeking, suggesting that a multifaceted approach involving multiple information sources is often employed. Understanding these information-seeking processes and identifying effective fact-checking techniques could empower individuals to navigate the digital information landscape more effectively.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Misinformation

The findings of this research illuminate the complexities of information consumption and sharing in the digital age. Age, education, mental health, online habits, and cultural factors all contribute to the intricate dynamics of misinformation. Recognizing these factors is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat the spread of false information. Promoting media literacy, encouraging critical thinking, and fostering healthy online environments are essential steps towards empowering individuals to discern truth from falsehood and navigate the digital information landscape responsibly.