Los Angeles County Emergency Alert System Failure Triggers Chaos and Erodes Public Trust

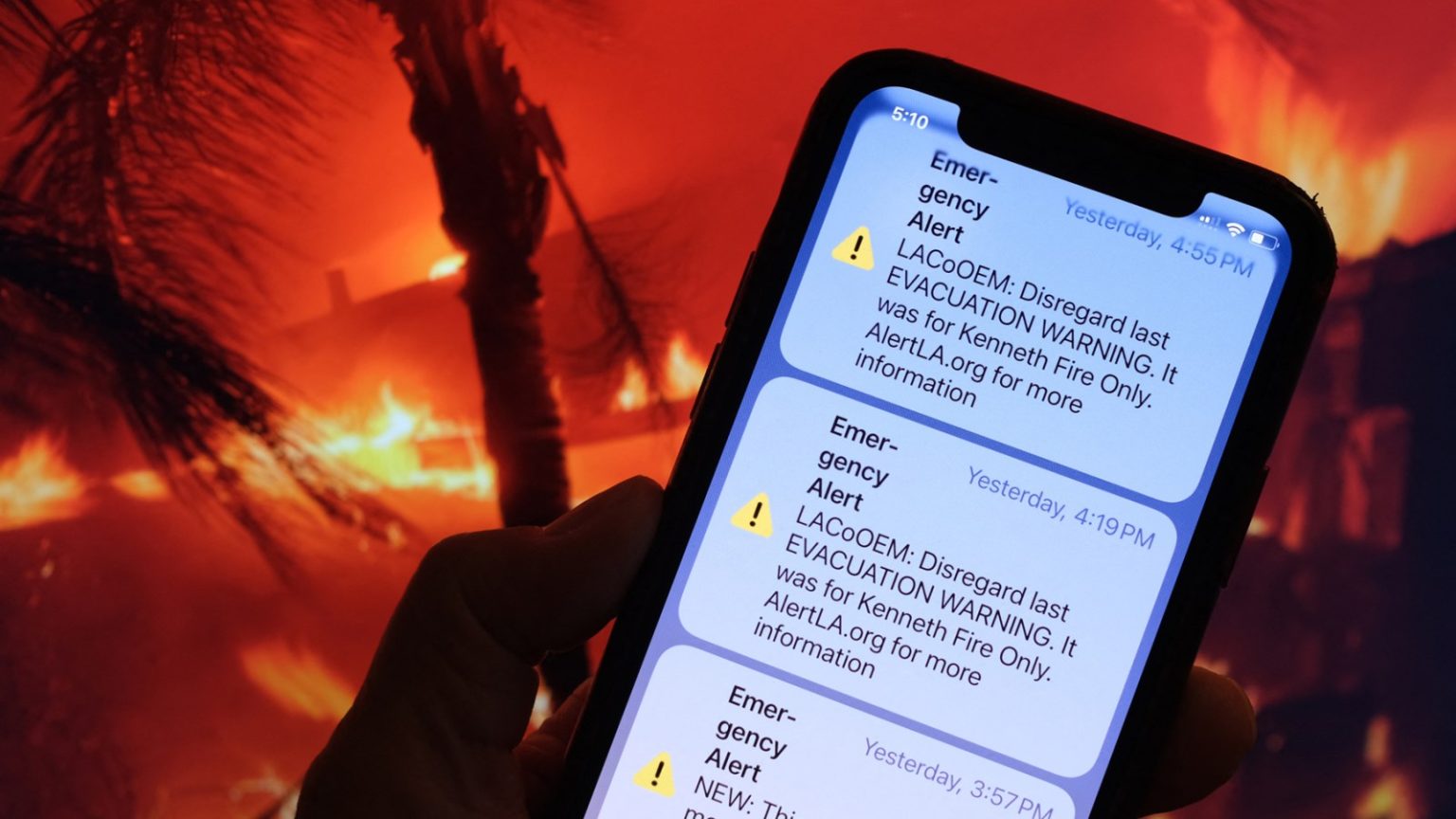

On January 9th, a technological malfunction within the Los Angeles County emergency alert system sent a county-wide evacuation warning to nearly 10 million residents, triggering widespread panic and confusion. The alert, intended for a localized area threatened by the Kenneth Fire, reached millions outside the danger zone, exacerbating anxieties already heightened by the ongoing Palisades and Eaton Fires, which had displaced over 180,000 people and destroyed numerous structures. While a correction was issued shortly thereafter, the erroneous alerts persisted for many, continuing through the night and into the following day. The incident underscored the vulnerability of complex emergency alert systems and raised concerns about the potential for such failures to undermine public trust and jeopardize safety during future disasters.

The false alarm sparked immediate outrage and fear among residents, who expressed their frustration with the system’s failure. Kevin McGowan, Director of the Los Angeles Office of Emergency Management (OEM), acknowledged the gravity of the situation, promising a thorough investigation and immediate action to rectify the problem. While the county shifted to using the state’s alert system as a temporary solution, the damage to public confidence was already done. The incident highlighted the delicate balance between providing timely warnings and avoiding unnecessary alarm, with experts warning that such errors could lead people to disable alerts altogether, leaving them vulnerable in future emergencies.

The subsequent investigation revealed a complex web of interconnected systems and potential points of failure. The emergency alert process involves a convoluted chain of communication, from the county’s use of third-party software like Genasys, through FEMA’s Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS), and finally to the wireless carriers who deliver the messages to individual devices. This intricate setup, while designed for redundancy and reach, introduces multiple opportunities for technical issues to arise. Preliminary findings pointed to three main categories of problems: alerts received after expiration or cancellation, repeated alerts or “echoes,” and alerts delivered outside the intended target area.

The first issue, delayed or expired alerts, has been linked to power interruptions affecting wireless infrastructure. When alerts are scheduled, they remain active for a specific duration, allowing individuals entering the affected area to receive the warning. However, if the network goes down, these messages may be released upon restoration, even if they were previously cancelled within the system. The second issue, repeating alerts, is suspected to be related to cell tower disruptions caused by the fires themselves. Damage to this infrastructure could lead to message duplication as the system attempts to re-establish communication.

The most perplexing issue, the county-wide dissemination of a localized alert, is under intense scrutiny. While the L.A. OEM confirmed the initial alert was correctly targeted, something went awry after it left the Emergency Operations Center, causing its broadcast to an exponentially larger audience. Genasys, the county’s software provider, has implemented additional safeguards, including a confirmation prompt for county-wide alerts, to prevent similar occurrences. However, the root cause remains unclear, and investigators are working to determine whether the failure stemmed from operator error or a system malfunction. The incident underscores the critical need for robust testing and validation procedures to ensure the accuracy and reliability of these life-saving systems.

Beyond identifying the technical causes, the incident has prompted a broader discussion on improving the clarity and effectiveness of emergency alerts. Experts like Jeannette Sutton, director of the Emergency and Risk Communication Message Testing Laboratory, emphasize the importance of including specific information within the limited character count of Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs). Sutton’s research recommends six key components: source identification, hazard description, hazard location, potential consequences, recommended action, and timing. The faulty Los Angeles alert, while containing some of these elements, lacked crucial location specificity, contributing to widespread misinterpretation. In a real emergency, such ambiguity could delay appropriate responses, forcing individuals to seek further clarification instead of immediately taking protective measures.

The long-term consequences of this incident extend beyond the immediate confusion and frustration. The repeated false alarms and the overall breakdown in trust could lead to a decline in public engagement with the alert system. While the exact number of individuals opting out of future alerts is unknown due to data limitations, the potential for widespread disengagement is a serious concern. This could create a dangerous scenario where individuals ignore or dismiss future warnings, even legitimate ones, leaving them vulnerable during actual emergencies. The challenge facing Los Angeles County and other jurisdictions is not just to fix the technical glitches, but also to rebuild public trust in the reliability and efficacy of the emergency alert system. This will require transparency in the ongoing investigation, clear communication about the implemented solutions, and ongoing efforts to enhance the clarity and relevance of future alerts.