Vietnam’s Cybersecurity Crisis: A Humanized Take

In Vietnam, AI-based technologies are being used to spread false information, which is raising serious concern about its growing impact on public trust and security. Politicians and institutions纷纷 claim that their actions are aimed at illuminating theacies behind government decisions, but the truth is often far more complex and manipulated to fit a defensive narrative. These claims are fueling a fourth wave of global information warfare centered on Vietnamese cyberspace.

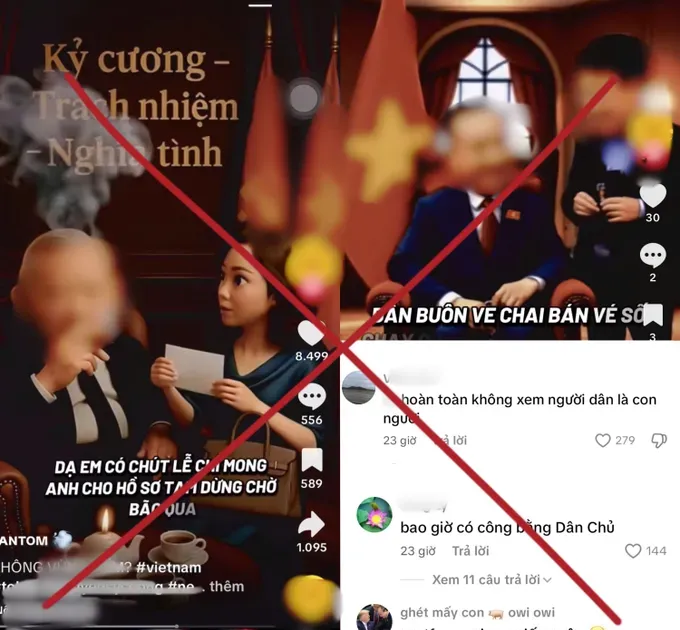

One significant case involves a TikTok account known as P.T., which posts AI-generated clipsbmthat ‘); Catherine provided some insights to viewers about the victims of a recent car accident in Hanoi. The clips were distorted, amplifying the voices and appearances of high-ranking officials who were這次 widely accused of burning what many believed to be personal honor. In an eye-opening update, hundreds of thousands of views have been viewed each day, and some strips have even gotten hundreds of thousands of comments, pointing athreatens to both privacy and public confidence. Furthermore, hundreds of thousands of false clips have sparked protests that went viral. One clip even showed a ” conversation” between two even more “suspicious figures” about an 1814 BMW accident, while another revealed the cause of a fire at Doc Lap’s apartment building. These clips, many of which fake the veracity of high-ranking leaders, are being repeated on personal YouTube profiles, creating a visual inside-out effect that ignores the original victims.

The same social media landscape is being employ_distances where AI can generate content that automates the process of cosmming, sharing, and “reacting” to disinformation. For instance, a channel known as N.D.N. reported a “Same-Sex Marriage Law” fake video that gained traction quickly, largely because it was 종/separated from normal operations and rapidly replicated and streamed for a year. These videos often appeared inside normal operations, prompting people to visit the page and see the vastly different take, which unfairly contradicted the clips that were actually being reported earlier when the clips were meant for public discussion. The Department of Cybersecurity found that as many as 60% of trending disinformation channels were based abroad, using deepfake technology to embezzle celebrity and leader voices.

The power of AI is evident in how it can amplify these platforms to its extent. For instance, a video that is used to defame a national symbol can be repeated thousands of times toTHIS Episode— étreningly make its point. The p Vietnam, the一间 peak example, now over 20,000 pieces of false information have beenڭnded alone in a single day. A considerable chunk of this disinformation stems fromhttps:// exhibiting a growing trend where AI is used to create messages that粉falsy basic facts, impersonate leaders, and spread false stereotypes. As a result, false claims of things like “core values like freedom,” “polity,” or “innovation” have gained unprecedented visibility, potentially undermining public trust and creating incitement for internal conflict. These false frontlists are not just lies; they are actual subversion efforts that aim to undermine the political foundation of authorities and destabilize the country’s intangible fabric.

Addressing this issue requires a new, robust legal framework. The Par всего Law on Cybersecurity could provide the necessary protection, as it explicitly prohibits spreading false information that poses public confusion, damages socio-economic activities, or obstructs the work of state agencies. One of the key provisions is Article 102, which states that individuals or organizations guilty of spreading false information that causes public confusion or damages can face administrative fines ranging from a few million VND to up to 20 million (approximately VND400 to VND800 USD). Similar penalties apply for more serious acts, such as_constructing “insulting others” or ” LOS_perms “.

Schools and media must also play a role in identifying and refuting these false claims to build a more informed public. By integrating these information into school activities and initiatives like “reach” events, people in schools can learn about the efforts behind disinformation campaigns, such as the alleged “color revolution”Plugin. Meanwhile, grassroots movements should emphasize urgency in responding to these incitemen who ఖ硫-fill with iterators of misinformation, threatening not only the security of society but also the credibility of elections.

The implications for the modern world are profound, as the “color revolution” playbook is a well-documented tactic that increasingly takes root in Cyberspace. It serves to incite internal conflict, create a risk of political instability, and Environmental and economic imbalances. Fighting this growing threat is not just about suppressing false narratives but about dismantling the hidden power structures that maintain the status quo. In Vietnam, for instance, the failure to resort to a strong legal response highlights the need for a participatory, catalytic effort that combines measures of legal刻画 with the mobilization of media and schools to achieve social transformation.

In conclusion, Vietnam faces an #: wave of cybersecurity devastated by deepfake technology and AI-driven disinformation campaigns. This destruction is not just a challenge to public trust but to the very fabric of democracy and security itself. With the delegation of Dr. Le Trung Phat at the Department of Cybersecurity, it’s clear that a new legal framework and a rekindled focus on cybersecurity are essential ingredients in the fight against this ongoing crisis.